On Heaven, Earth, Hell by Eunsong Kim

October 20, 2023

Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien, Langit Lupa (Heaven and Earth), 2023. Film still. Courtesy of the artists.

Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien’s 2023 experimental documentary, Langit Lupa (Heaven and Earth), opens up on a plane of polychromatic green land. Some of the greens of the grass are grayed, and the mountain holds a distant bluish tint. In writing about the landscape of the island of Negros, the region featured in the documentary and well known in the Philippines for its sugar production, Camacho and Lien describe “…field after field of cane. These fields possess no lush beauty” (1). This absence can be explained by the abundance of chemical fertilizers deployed to tend the nutrient-depleted soil, on which nothing would otherwise grow.(2) In this, the two artists remark on how the sugar industry “tends towards entropy.”(3) Thus, in the opening shots of the film, though the sugarcane plants hold the darkest hues, under the heavy presence of chemical fertilizer, it would be disingenuous to describe them as lush.(4)

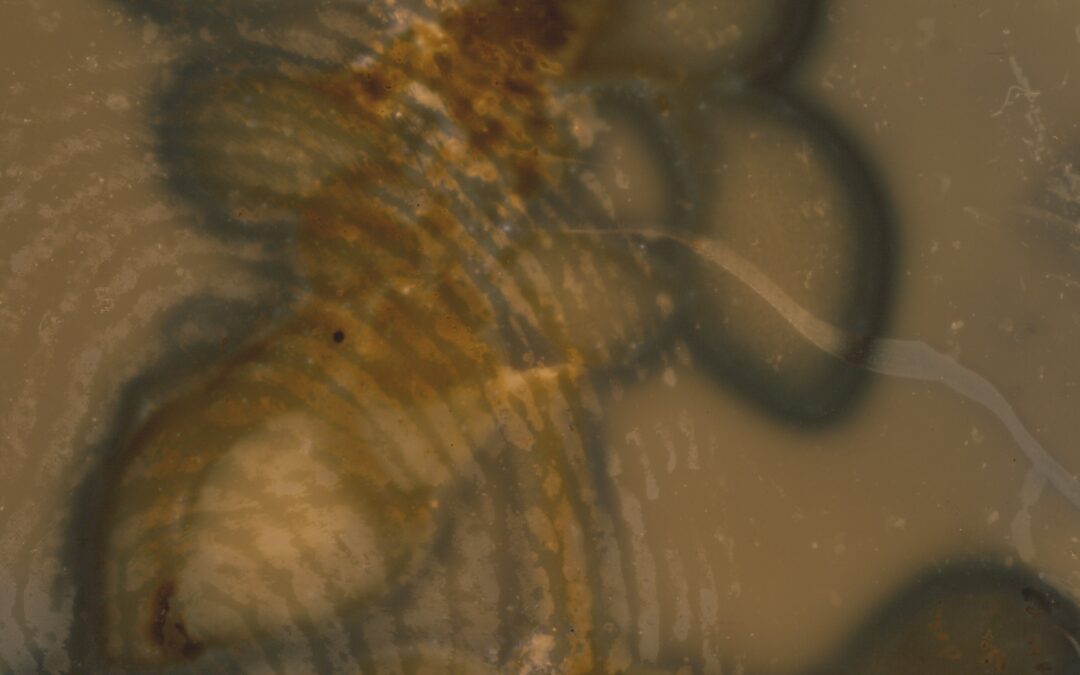

Rather than aestheticized encounters with abstracted landscapes, the documentary offers the audience with histories and memories about the land, voiced by survivors of the Escalante Massacres of 1985. Visiting Ninita Orot grave’s at the public cemetery, also surrounded by a sugarcane plantation, a speaker remarks on how there is “so much grass,” while a ring of children chant a nursery rhyme: “Langit, Lupa, Impiyerno (Heaven, Earth, Hell),” which ends with the line, “Who will leave your mother’s place?.” Cut between shots of fields, a butterfly lays still on a desiccated strip of felled sugarcane, and as the survivors speak, phytograms begin to appear. Phytograms are a type of photographic emulsion, which use organic materials as central to the development and image making process. Botanical matter is deployed to stimulate chemical reactions that allow images to form. The artists, who began to make phytograms in Negros alongside their production of the film, describe the process as such: “Plants are soaked in a solution of Vitamin C and washing soda, which activates a phenol chemical within the plant, allowing it to act as a developer for photosensitive material. When the plants are laid on the film stock, it leaves a chemical trace.”(5)

Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien, Langit Lupa (Heaven and Earth), 2023. Film still. Courtesy of the artists.

Phytograms utilize the plants as model, subject, object, colorist, and developer. The phytograms of leaves bitten by insects create intricate images and provide details about the interior workings of the land that the camera cannot capture. And the moments in which they appear move quickly in flashes and are elongated through repetition. Not quite sepia toned, with clusters of dark lines, splatters of dots with ring shadows that whirl like trace fragments, the phytograms hold a distinctive space for the survivors to speak. As bits of overexposed white light sneak through some of the frames, the viewer can spot parts of the original matter, but never its whole. The enigmatic imagery, woven together with survivor memories of their lost ones, the history behind their protests and present day feelings, asks the viewer to hear what we may not know, while visually reminding us what cannot be known. The phytograms create this visceral experience, and Lien describes how through them, “the viewer is invited to project something onto the wild micro terrains made by this merging of plant and film.” The coupling of landscape scenes with the phytograms may be a way to understand the edifice of the documentary. From couplets of laborers tending to the sugarcanes and children playing in the fields pulling on the crops, to the phytograms in which the survivors speak, the relationship between land extraction, labor dispossession, and the expropriation of life become distilled and unfastened. Small, isolated microorganisms from the land are tended to with the deepest focus, and the land from which the objects serve as the documentary’s main visuals. This oscillation, between wide angled shots and the intimacy of the intercut phytograms, becomes the portal through which one grapples with the politics of the documentary, and the stakes of remembering the Escalante Massacre.

It seems important to note that this is not just a film about a massacre, but also about a powerful mass protest.(6)

—Enzo Camacho

How does one contend with documentation of a massacre? My engagement with Camacho and Lien’s documentary bears much trepidation. As in, the project is too urgent, and the voices featured too critical to speak of lightly. The ways in which the artists engage with survivors remind me of Lisa Yoneyama’s writing in Hiroshima Traces, and her position on the limits of mimetic representation and thus the importance of listening.(7) In writing about representations about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and her interviews with survivors and the documentaries in which they’ve appeared, Yoneyama situates the survivors’ memories as both history and political desire. She cautions against that which distorts “forgetting” with “remembering” which too often happens in the form of state commemorative monuments. Such monuments frequently signal a conclusion to the past, enacting the official erasure of people and their memories which produces the “taming of memory.”(8)

And perhaps as an antidote against this potential “taming,” the interviews in Langit Lupa arrive almost wholly unfiltered. When I ask the artists where they locate themselves in the interviews, Camacho responds that they see themselves as present in material ways, from how “our literal fingerprints are imprinted in some of the phytograms,” to the ways in which their bodies shape the camera’s framing, to the ambient sounds of their voices towards the end of the film. What became central for the artists was prioritizing an ongoing long-term relationship with the community, with those who appear on and off screen. They also tell me that the documentary was survivor-activated, and thus the explicit politics of the film is survivor-driven. The collaborative practice in the film’s making configures art as a tool for critical listening, and its circulation a weapon for the life of their memories.

Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien, Langit Lupa (Heaven and Earth), 2023. Film still. Courtesy of the artists.

And simultaneously, there are still the limitations of representation—as Yoneyema suggests––a limitation of which many of the survivors seem critically aware. In this regard Camacho notes that “A film is not self-sufficient…what matters is how you situate your work…and which social forces these practices serve within a wider field of struggle.” Corresponding to the present field of struggle, in an earlier work, Camacho and Lien locate the histories of Peasant Resistance in the Philippines, and Negros in particular, by describing Bungkalan—the practice of “hacienda workers…independently cultivat[ing] small pockets of their masters’ idle lands to grow sweet potatoes, pigeon peas, eggplant, okra, water spinach, and other crops…” for their own sustenance and in resistance to Tiempo Muerto.(9) Tiempo Muerto, the period considered “dead time,” describes both the moments between the harvest and its planting and how the hacienda workers are paid only for the time labored directly in the field, and not the precarious life required for this labor.

Bungkalan is a practice against the force of dead time, which akin to dead labor, imprints the workers’ irregularity, and how their lives become affixed to the end and life of a crop, uncredited to its living. A speaker in Langit Lupa extrapolates on the compression and composition of Tiempo Muerto, and how in Hiligaynon, the language of the workers, there are two kinds of hunger Bungkalan addresses. Gutom is the regular hunger one might feel when needing to eat, and tigkiriwi is “when the hunger goes on for days and weeks — the hunger that gnaws at the guts, when your stomach and brain moan together.” Tigkiriwi, the viewer can surmise, arises from the conditions the hacienda workers faced before the Escalante Massacre, and tigkiriwi remains the condition of labor.

Against state permission, this experiment in documentary-making remembers both hungers alongside the massacre. Lien emphasizes the risks taken by these survivors and why the film insists on their anonymity. As she remarks, “The victim’s memories of the Escalante Massacre are contested narratives under state-sanctioned national history.”(10) Their accounts of tigkiriwi propel a politics against the violence that produces this hunger, and mark how desires for the dead, and the appetite towards living might take the difficult form of collective and communal remembrance. In discussing the archival practices of youth activists who protested the violent suppression of peasants and left-wing students in Indonesia, Doreen Lee writes, “Remembering one’s discordant past or the nation’s submerged past is disruptive work, for remembering mars the surface of normality…and can make the survival of survivors that much harder.”(11) Remembering, Lee contends, is not practiced with ease by survivors and is nevertheless prioritized. When a speaker in the film states, “Here, when we visit our dead, it’s a family affair,” and “I wish I didn’t have to remember because it makes my chest hurt” yet insisting, “until I die, I will never forget,” composite familial gatherings are assiduously practiced as ritual and in perpetuity across temporalities.

Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien, Langit Lupa (Heaven and Earth), 2023. Film still. Courtesy of the artists.

Writing about the memorials constructed to honor victims who “lived and died in defiance” of Ferdinand Marcos’ dictatorship, Josen Diaz writes, “I search for ways to name the dead and the living that do not over determine their being and becoming in the world.”(12) Akin to searching for names and holding their becoming, the illocutionary phytograms travel between past and present, braiding timescales. Camacho describes, “Following the survivor testimony narrating the moment when the paramilitary troops started shooting, we wanted to make it almost seem as if the phytograms are ‘performing’ or ‘reenacting’ the violent scene, so that there is a kind of collapse of timescales and registers, between the violence that has been inflicted on the land over centuries, and this specific incident of human violence.”(13) Langit Lupa gives as much as it demands: to hold the difficulty of remembrance, to listen rather than to identify, to interrogate rather than abandon, to hear memories as part of the land, to situate historical desire with critique, to push against the ease of clarity, against the expectation of artistic resolution—towards the widest fields—

Footnotes

- “The Angry Christ.” Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho. How to Relate, ed. Hanna Magauer et. al. transcript Verlag, 2021, p. 59.

- Ibid., 59.

- Ibid., 59.

- On this note, Ami Lien reminds me of journalist Edgar Kadagat’s opening remarks in the documentary on the relationship between US deforestation and the rise of sugar plantations-particularly when he says, “It was a massacre of the jungle. A massacre of the environment.”

- Description of phytograms from the artist Ami Lien, with a note that this is a relatively new term coined by artist Karel Doing.

- Interview with the artist, August 2023.

- Yoneyama states, “We must seriously consider and appreciate survivors’ insistence on telling the past as it really happened, despite their keen awareness of the limits of mimetic representation.” And simultaneously, “We must also rethink…beyond the alleged objective of establishing historical knowledge.” Yoneyama, Lisa. Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory. University of California Press, 1999, p. 212.

- In situating the “taming of memory,” Yoneyama writes of the initial planning of the “Peace Tower,” or what became known as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. The commemorative site was first proposed with an entertainment and shopping arcade; she also writes of the various projects the city officials planned to revitalize the city, including “municipal festivals” and “tourism promotion.” Under the tutelage of victims and survivors, the state insisted on suppressing memories of the past in order to rush towards a limiting future. See Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory, p. 43-44.

- Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien, Surviving Tiempo Muerto, Walker Museum, April 2022.

- Interview with the artist, August 2023.

- Lee, Doreen. Activist Archives: Youth Culture and the Political Past in Indonesia. Duke University, 2016, p. 20.

- Diaz, Josen. Postcolonial Configurations: Dictatorship, the Racial Cold War, and Filipino America. Duke University, 2023, p. 8.

- Interview with the artist, August 2023.

About the Artist

Eunsong Kim

Eunsong Kim is an Associate Professor in the Department of English at Northeastern University. Her practice spans: literary studies, critical digital studies, poetics, translation, visual culture and critical race & ethnic studies. Her writings have appeared in: Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, and in the book anthologies, Poetics of Social Engagement and Reading Modernism with Machines. Her poetry has appeared in the Brooklyn Magazine, The Iowa Review, Minnesota Review amongst others. She is the author of gospel of regicide, published by Noemi Press in 2017, and with Sung Gi Kim she translated Kim Eon Hee’s poetic text Have You Been Feeling Blue These Days? published in 2019. Her forthcoming academic monograph, The Politics of Collecting: Race & the Aestheticization of Property (Duke University Press 2024) materializes the histories of immaterialism by examining the rise of US museums, avant-garde forms, digitization, and neoliberal aesthetics, to consider how race and property become foundational to modern artistic institutions. She is the recipient of the Ford Foundation Fellowship, a grant from the Andy Warhol Art Writers Program, and Yale’s Poynter Fellowship.